V8: Behind the Scenes (December Edition feat. WebAssembly and Real World Performance)

Following up on what I promised earlier here's another edition on what's going on behind the scenes of V8 as we are approaching the end of the year. A lot of cool stuff happened in V8 in 2016, probably most importantly that we are changing the focus of V8 to treat Node.js as a first class citizen (similar to Chrome) and moving away from measuring performance only via traditional JavaScript benchmarks to measuring actual performance of real world web pages via tooling built into the browser.

WebAssembly and asm.js #

Native WebAssembly support is expected to hit the stable versions of all four browsers in the first half of 2017, but since there's no polyfill available (partially because WebAssembly semantics for heap access are different from asm.js), only some big players on the web are expected to deliver native WebAssembly bytecode and a separate asm.js fallback based on browser feature detection; the majority of native code on the web users will likely continue to ship asm.js for the next two to three years (based on experience with other new web platform features).

Thus most users will not be able to benefit from the WebAssembly compilation and execution engine we built into Chrome directly. So we built a small wrapper around the WebAssembly component in V8, that allows it to also consume native code input via asm.js in addition to the native bytecode format. Two weeks ago we staged the new asm.js pipeline, which sends asm.js code through the new WebAssembly pipeline instead of the TurboFan JavaScript compiler pipeline, and executes the resulting machine code in the WebAssembly native execution environment. This allows you to leverage many of the benefits of WebAssembly today and brings ahead-of-time compilation (AOT) for asm.js to Chrome, with full backwards compatibility.

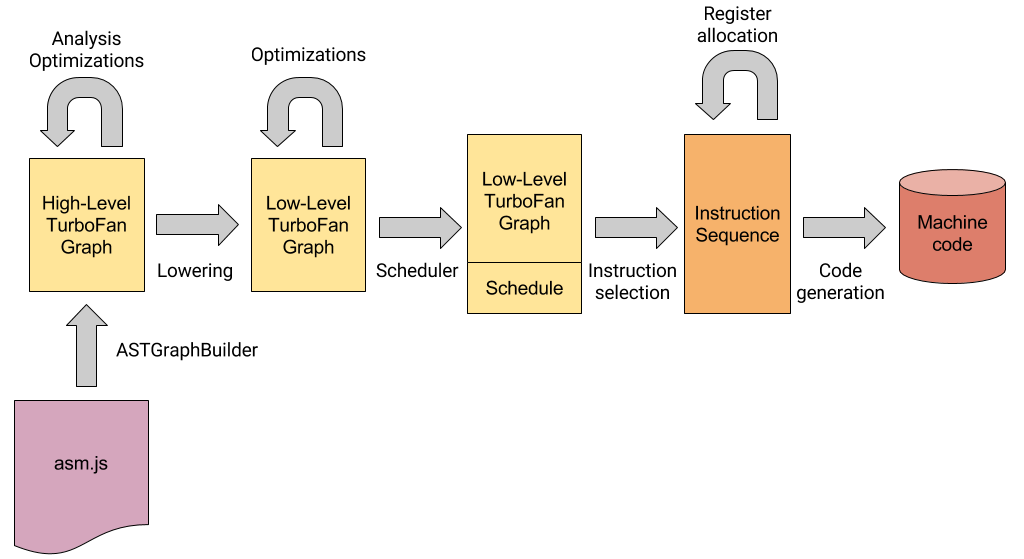

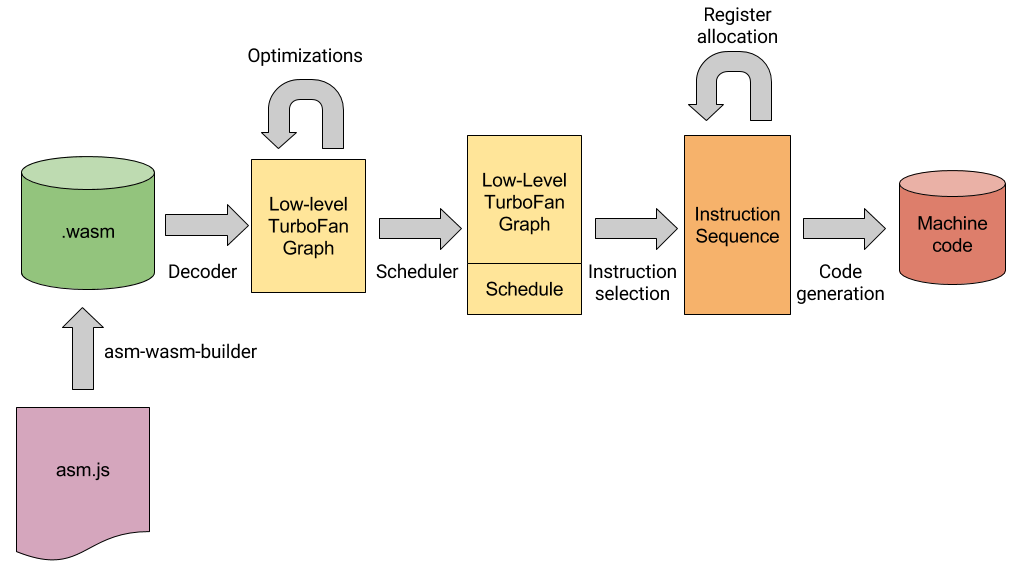

The WebAssembly compilation pipeline reuses some backend parts of the TurboFan compiler pipeline, and is therefore able to generate similar code, but with a lot less compilation and optimization overhead, and leveraging various benefits of the WebAssembly execution environment. For example, the asm-wasm-builder extracts the asm.js type annotation and uses those to generate typed WebAssembly code. If it hits any unsupported language constructs, it will just bail out and we will fall back to the TurboFan JavaScript compiler pipeline for this asm.js module. In contrast TurboFan must be able to deal with the whole EcmaScript 2017 language and can only consume a fraction of the static type information. For example consider the following asm.js module:

function Module(stdlib) {

"use asm";

function f(x) {

x = +x;

x = x * x;

return +x;

}

function g(x) {

x = +x;

x = +f(x);

return +x;

}

return { g: g };

}It contains two functions f and g, the latter being exported and callable by regular JavaScript code, i.e. g is an entrypoint to the asm.js module. g doesn't do much but calls f with whatever input you pass to g converted to a Number. According to the asm.js type annotations, f has type double -> double, but this information is only usable as long as the asm.js module validates, i.e. passes the type checks in the asm.js specification. The asm-wasm-builder does the necessary validation and is thus able to generate code that leverages this type information without having to perform type checks at runtime (type checks are still necessary on the boundary to JavaScript obviously). In this concrete example, the asm-wasm-builder knows after validation that f is only used internally in the asm.js module (i.e. it's not exported to JavaScript) and all call sites pass a double and expect a double as result. For example, let's run the module above through the new WebAssembly pipeline:

$ ~/Projects/v8/out/Debug/d8 --validate-asm --trace-wasm-decoder asm.js

[...SNIP...]

+0 local decls count : 00 = 0

local decls count: 0

env = 0x7f4fde004250, state = R, reason = initial, control = #1:Start

wasm-decode 0x7f4fddffebf3...0x7f4fddffec0c (module+92, 25 bytes) graph building

env = 0x7f4fde004278, state = R, reason = initial env, control = #11:Merge

@1 #20:GetLocal | d@1:GetLocal[0]

@3 #44:F64Const | d@1:GetLocal[0] d@3:F64Const

@12 #a2:F64Mul | d@12:F64Mul

@13 #21:SetLocal |

@15 #20:GetLocal | d@15:GetLocal[0]

@17 #20:GetLocal | d@15:GetLocal[0] d@17:GetLocal[0]

@19 #a2:F64Mul | d@19:F64Mul

@20 #21:SetLocal |

@22 #20:GetLocal | d@22:GetLocal[0]

@24 #0f:Return |

wasm-decode ok

[...SNIP...]

asm.js:1: Converted asm.js to WebAssembly: success

asm.js:1: Instantiated asm.js: success

This shows the WebAssembly bytecode generated for the function f. As you can see the code doesn't need to perform any type checks on the input; there's still a somewhat unnecessary F64Mul of x and 1.0 in there, but the TurboFan backend will eliminate this prior to code generation. The final code generated for f using WebAssembly looks like this:

-- B0 start (no frame) --

0x10a04e985b00 0 493ba5780c0000 REX.W cmpq rsp,[r13+0xc78]

0x10a04e985b07 7 0f8605000000 jna 18 (0x10a04e985b12)

-- B2 start (no frame) --

-- B3 start (no frame) --

0x10a04e985b0d 13 c5f359c9 vmulsd xmm1,xmm1,xmm1

0x10a04e985b11 17 c3 retl

-- B4 start (no frame) --

-- B1 start (deferred) (construct frame) (deconstruct frame) --

0x10a04e985b12 18 55 push rbp

0x10a04e985b13 19 4889e5 REX.W movq rbp,rsp

0x10a04e985b16 22 49ba0000000006000000 REX.W movq r10,0x600000000

0x10a04e985b20 32 4152 push r10

0x10a04e985b22 34 4883ec08 REX.W subq rsp,0x8

0x10a04e985b26 38 c5fb114df0 vmovsd [rbp-0x10],xmm1

0x10a04e985b2b 43 48bb10e4f40f317f0000 REX.W movq rbx,0x7f310ff4e410 ;; external reference (Runtime::StackGuard)

0x10a04e985b35 53 48bef93b5006492e0000 REX.W movq rsi,0x2e4906503bf9 ;; object: 0x2e4906503bf9 <FixedArray[255]>

0x10a04e985b3f 63 33c0 xorl rax,rax

0x10a04e985b41 65 e8bae6e7ff call 0x10a04e804200 ;; code: STUB, CEntryStub, minor: 8

0x10a04e985b46 70 c5fb104df0 vmovsd xmm1,[rbp-0x10]

0x10a04e985b4b 75 488be5 REX.W movq rsp,rbp

0x10a04e985b4e 78 5d pop rbp

0x10a04e985b4f 79 ebbc jmp 13 (0x10a04e985b0d)

0x10a04e985b51 81 0f1f00 nop

It first does a so-called stack check, which checks that we don't exceed a certain stack limit; besides guarding against stack overflows, this mechanism is used by Chrome to be able to interrupt the main thread of the renderer process, for example by DevTools, or to kill a tab that is executing an endless loop. The code then computes the square of the input, which is passed and returned in machine register xmm1 (WebAssembly has its own native calling convention that is slightly different from the usual platform calling conventions). Contrast this with the code generated via the TurboFan JavaScript compiler pipeline:

-- B0 start (construct frame) --

0x26d963005ec0 0 55 push rbp

0x26d963005ec1 1 4889e5 REX.W movq rbp,rsp

0x26d963005ec4 4 56 push rsi

0x26d963005ec5 5 57 push rdi

0x26d963005ec6 6 4883ec08 REX.W subq rsp,0x8

0x26d963005eca 10 493ba5780c0000 REX.W cmpq rsp,[r13+0xc78]

0x26d963005ed1 17 0f8657000000 jna 110 (0x26d963005f2e)

-- B2 start --

-- B3 start --

0x26d963005ed7 23 488b4510 REX.W movq rax,[rbp+0x10]

0x26d963005edb 27 a801 test al,0x1

0x26d963005edd 29 0f8566000000 jnz 137 (0x26d963005f49)

-- B8 start --

0x26d963005ee3 35 48c1e820 REX.W shrq rax, 32

0x26d963005ee7 39 c5f957c0 vxorpd xmm0,xmm0,xmm0

0x26d963005eeb 43 c5fb2ac0 vcvtlsi2sd xmm0,xmm0,rax

-- B9 start --

0x26d963005eef 47 498b85d80c0400 REX.W movq rax,[r13+0x40cd8]

0x26d963005ef6 54 488d5810 REX.W leaq rbx,[rax+0x10]

0x26d963005efa 58 49399de00c0400 REX.W cmpq [r13+0x40ce0],rbx

0x26d963005f01 65 0f866f000000 jna 182 (0x26d963005f76)

-- B11 start --

-- B12 start (deconstruct frame) --

0x26d963005f07 71 488d5810 REX.W leaq rbx,[rax+0x10]

0x26d963005f0b 75 4883c001 REX.W addq rax,0x1

0x26d963005f0f 79 49899dd80c0400 REX.W movq [r13+0x40cd8],rbx

0x26d963005f16 86 498b5d50 REX.W movq rbx,[r13+0x50]

0x26d963005f1a 90 488958ff REX.W movq [rax-0x1],rbx

0x26d963005f1e 94 c5fb59c0 vmulsd xmm0,xmm0,xmm0

0x26d963005f22 98 c5fb114007 vmovsd [rax+0x7],xmm0

0x26d963005f27 103 488be5 REX.W movq rsp,rbp

0x26d963005f2a 106 5d pop rbp

0x26d963005f2b 107 c21000 ret 0x10

-- B13 start (no frame) --

-- B1 start (deferred) --

0x26d963005f2e 110 488975f8 REX.W movq [rbp-0x8],rsi

0x26d963005f32 114 48bb10f4ddd8da7f0000 REX.W movq rbx,0x7fdad8ddf410 ;; external reference (Runtime::StackGuard)

0x26d963005f3c 124 33c0 xorl rax,rax

-- <asm.js:3:13> --

0x26d963005f3e 126 e8bde2e7ff call 0x26d962e84200 ;; code: STUB, CEntryStub, minor: 8

0x26d963005f43 131 488b75f8 REX.W movq rsi,[rbp-0x8]

0x26d963005f47 135 eb8e jmp 23 (0x26d963005ed7)

-- B4 start (deferred) --

0x26d963005f49 137 488975f8 REX.W movq [rbp-0x8],rsi

0x26d963005f4d 141 488b4510 REX.W movq rax,[rbp+0x10]

0x26d963005f51 145 e86a2cefff call ToNumber (0x26d962ef8bc0) ;; code: BUILTIN

0x26d963005f56 150 a801 test al,0x1

0x26d963005f58 152 0f8407000000 jz 165 (0x26d963005f65)

-- B5 start (deferred) --

0x26d963005f5e 158 c5fb104007 vmovsd xmm0,[rax+0x7]

0x26d963005f63 163 eb8a jmp 47 (0x26d963005eef)

-- B6 start (deferred) --

0x26d963005f65 165 48c1e820 REX.W shrq rax, 32

0x26d963005f69 169 c5f957c0 vxorpd xmm0,xmm0,xmm0

0x26d963005f6d 173 c5fb2ac0 vcvtlsi2sd xmm0,xmm0,rax

0x26d963005f71 177 e979ffffff jmp 47 (0x26d963005eef)

-- B7 start (deferred) --

-- B10 start (deferred) --

0x26d963005f76 182 c5fb1145e8 vmovsd [rbp-0x18],xmm0

0x26d963005f7b 187 ba10000000 movl rdx,0x10

0x26d963005f80 192 e81bcdf4ff call AllocateInNewSpace (0x26d962f52ca0) ;; code: BUILTIN

0x26d963005f85 197 4883e801 REX.W subq rax,0x1

0x26d963005f89 201 c5fb1045e8 vmovsd xmm0,[rbp-0x18]

0x26d963005f8e 206 e974ffffff jmp 71 (0x26d963005f07)

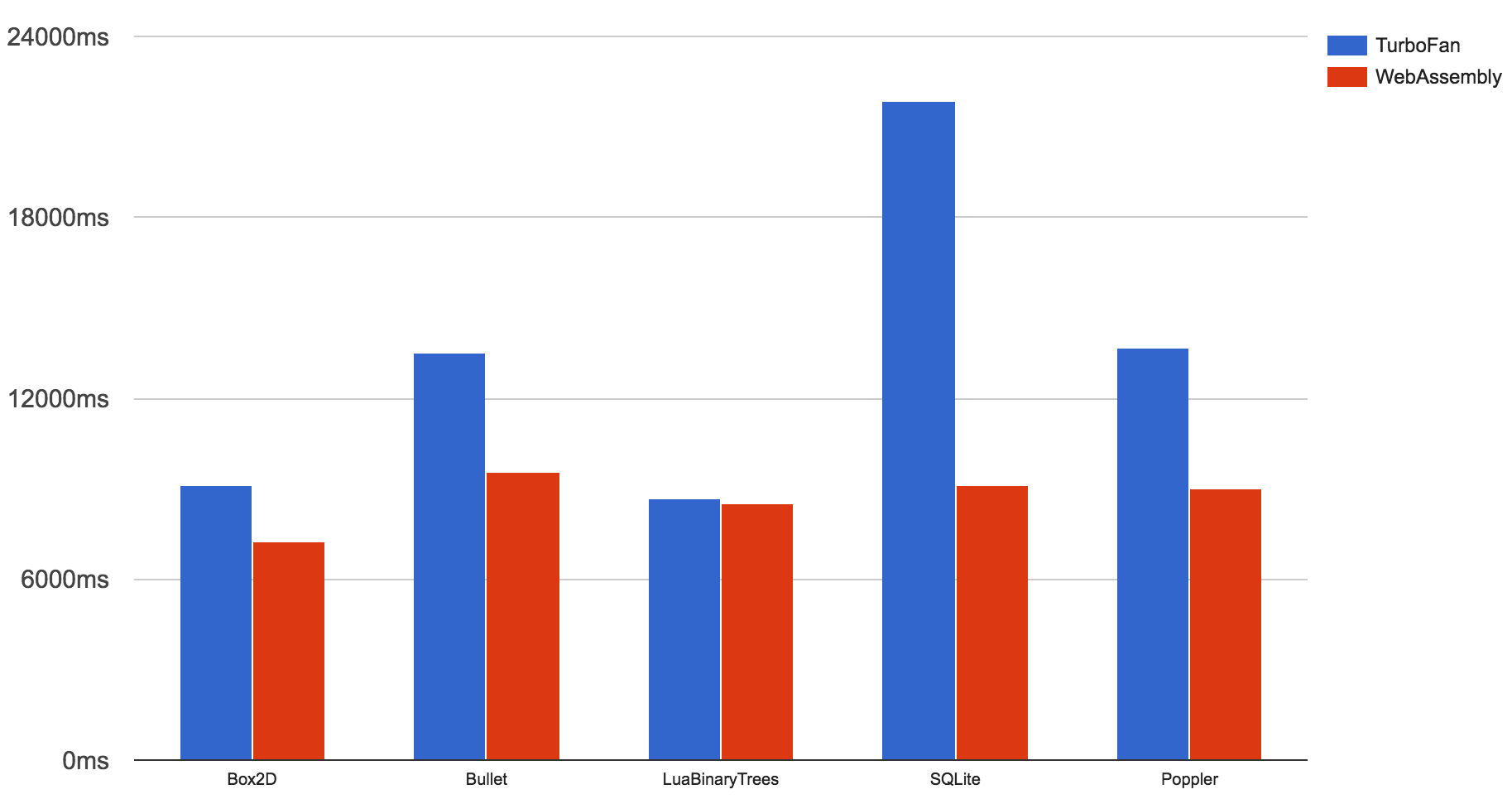

It's a lot heavier since it has to use the JavaScript calling convention and the uniform tagging scheme, and it has to perform type checks and conversions on the input x, and in the end has to allocate a HeapNumber for the resulting value. This translates to a huge improvement in execution speed of bigger applications, which tend to consist of a lot of small to medium sized functions that are called very often, where having native calling conventions helps a lot. For micro-benchmarks that spend most of their time in a single loop or at least a single function, it is unlikely that you experience a lot of benefits from having asm.js code take the WebAssembly pipeline, because the TurboFan type inference does a great job at eliminating almost all type checks.

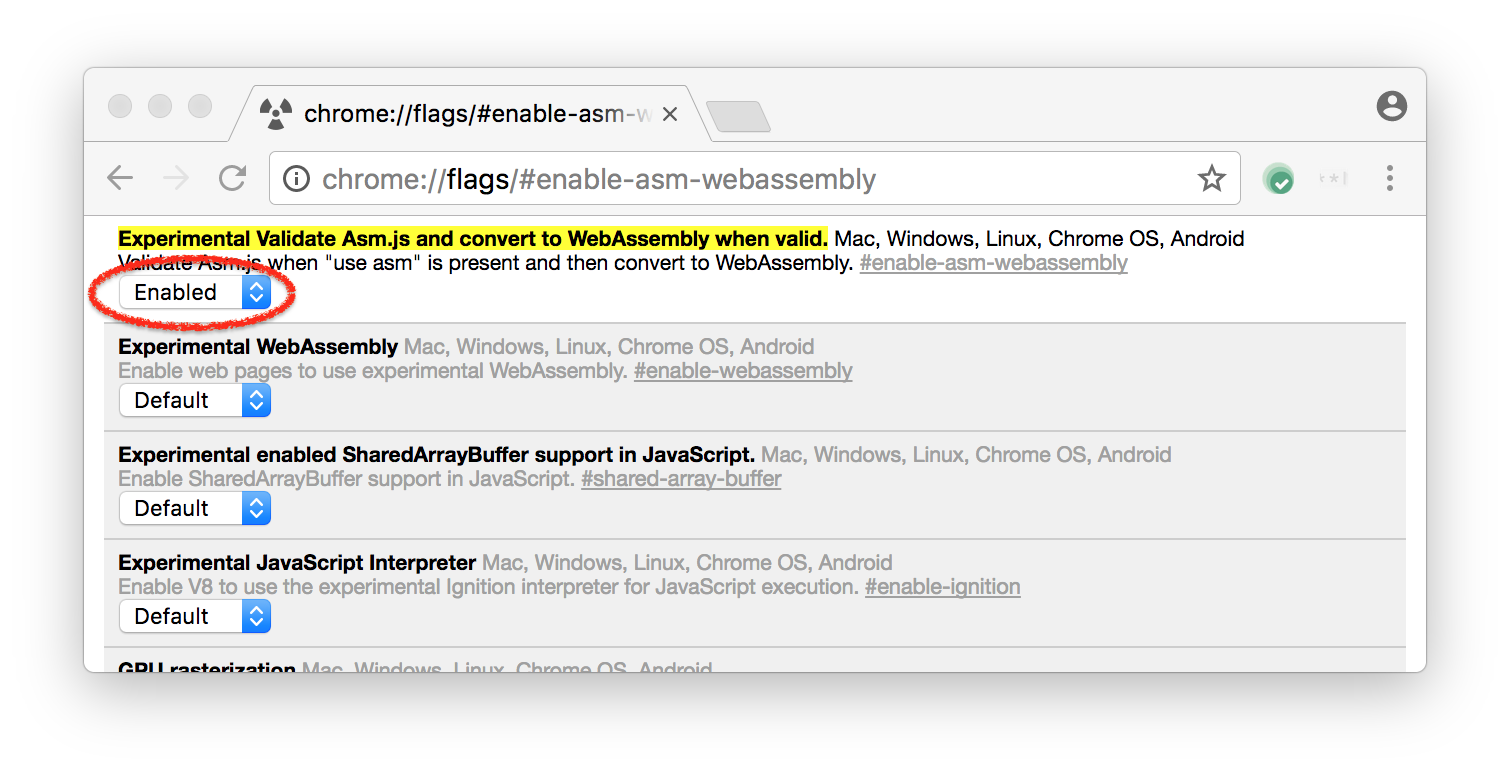

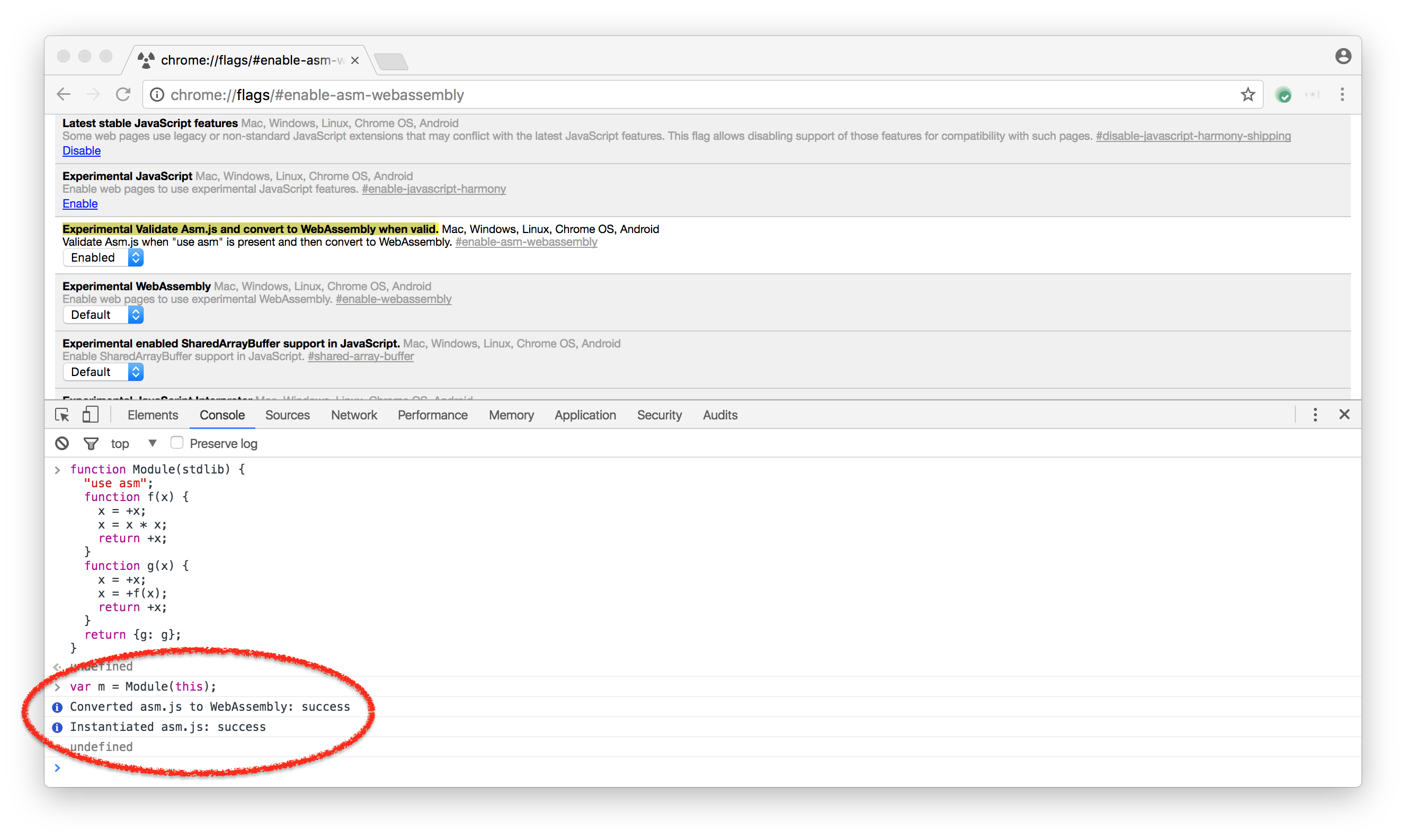

If you are running Chrome dev or canary channel, you can give it a try by enabling the experimental flag Experimental Validate Asm.js and convert to WebAssembly when valid and restarting Chrome.

The asm-wasm-builder will log information about asm.js module validation to the Chrome Developer Tools console, similar to what Firefox does, so you can easily verify that a certain asm.js module is recognized as valid:

We expect to be able to enable this by default in early 2017 unless we hit some terrible stability or security problems.

Real world performance measurements #

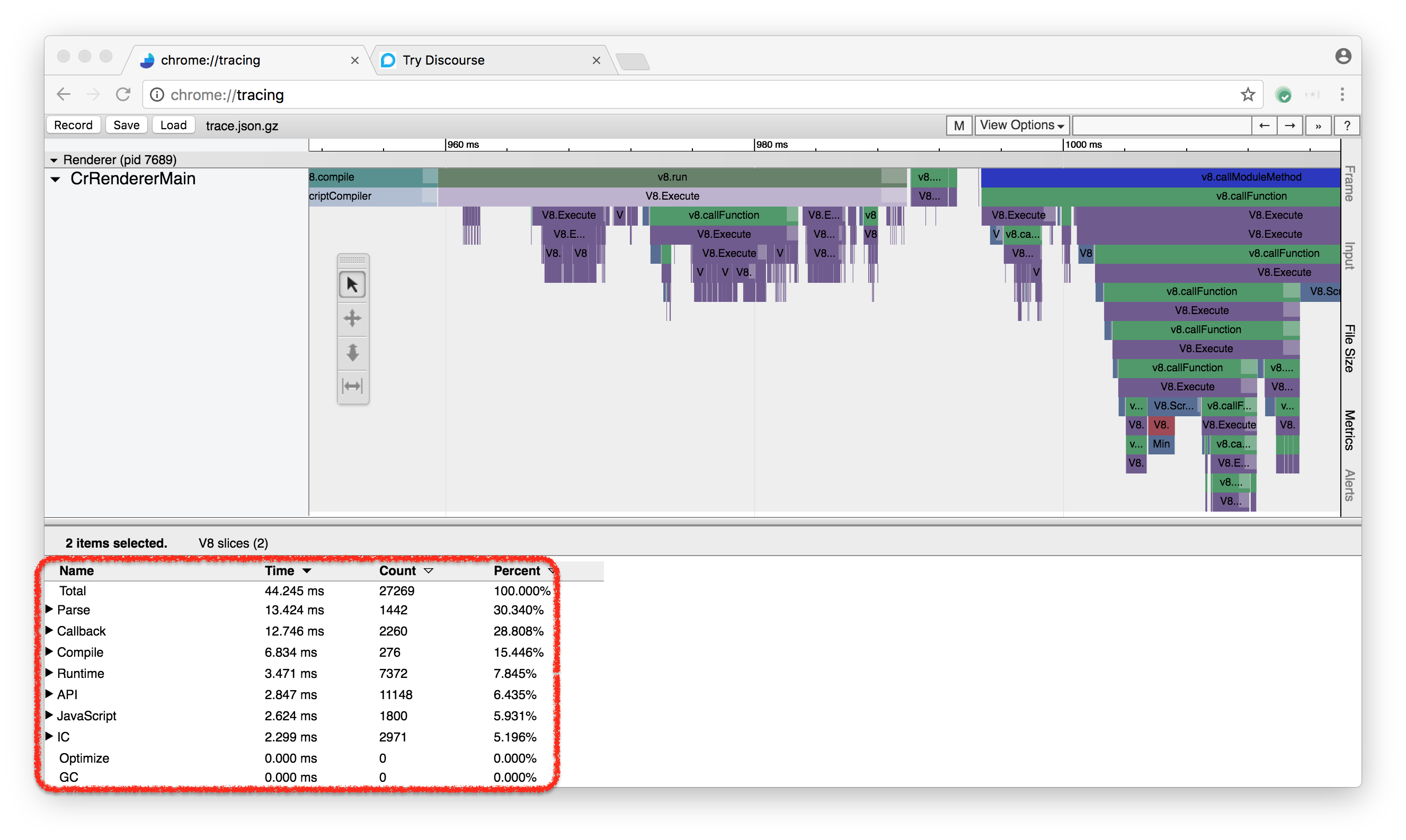

As mentioned in my blog post about JavaScript benchmarks, we've been investigating a lot in techniques to properly measure real world performance, especially on the web. We've added a lot of tracing support to V8 and Chrome for that, especially also tracing various internals of V8. One of the new tracing options is the so-called Runtime Call Stats in V8, which collects precise timing information for all V8 components. This is accessible via chrome://tracing and gives you pretty detailed information about where time in V8 is spent.

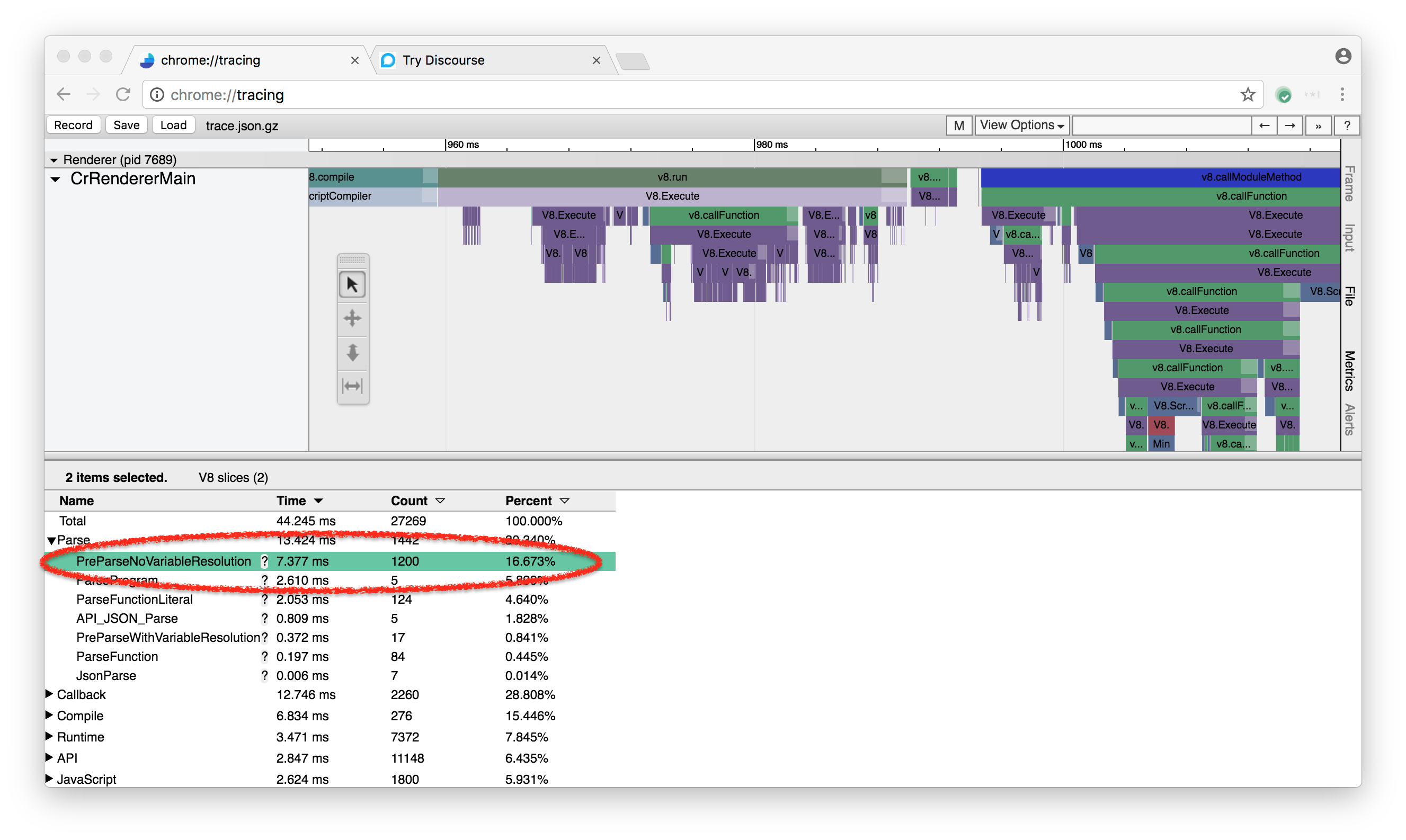

Currently this requires quite a bit of knowledge about V8 to really draw useful conclusions from this, but we're working on better integration with the developer tools in Chrome (i.e. by exposing the stats via lighthouse). Initially it was mostly useful for us internally since we had to understand where todays web pages spent most of their time in V8, but nevertheless you can probably still use some of the data that is gathered. For example you can check how much overall time is spent preparsing your scripts:

This is a good indicator whether your JavaScript bundles are bigger than they should be. For example in case of the discourse demo page we have to preparse 1217 times, but parse only 213 times. This doesn't automatically mean that only 1/6th of the overall script bundles are being needed due to the way that parsing works internally in V8, but it's an indicator that looking into script size might be a good investment of the developers time.

We plan to make these measurement tools more accessible during 2017 and provide developers with better insight into V8 performance. We also plan to continue our effort to focus on real world performance improvements rather than looking at benchmarks only, which was the main driver in the past.

If you haven't done so, be sure to watch the BlinkOn 6 talk on Real-world JavaScript performance from my colleagues Toon Verwaest and Camillo Bruni.

Update #

Apparently there's a slide deck from my colleagues Camillo Bruni from the V8 runtime team and Michael Lippautz from the V8 GC team that describes how to get to the Runtime Call Stats and the Heap Stats in chrome://tracing.

It should give you a rough idea how to use the new functionality in Chrome.