Faster async functions and promises

This article was originally published here, co-authored by Maya Lekova.Asynchronous processing in JavaScript traditionally had a reputation for not being particularly fast. To make matters worse, debugging live JavaScript applications — in particular Node.js servers — is no easy task, especially when it comes to async programming. Luckily the times, they are a-changin’. This article explores how we optimized async functions and promises in V8 (and to some extent in other JavaScript engines as well), and describes how we improved the debugging experience for async code.

Note: If you prefer watching a presentation over reading articles, then enjoy the video below! If not, skip the video and read on.

A new approach to async programming #

From callbacks to promises to async functions #

Before promises were part of the JavaScript language, callback-based APIs were commonly used for asynchronous code, especially in Node.js. Here’s an example:

function handler(done) {

validateParams(error => {

if (error) return done(error);

dbQuery((error, dbResults) => {

if (error) return done(error);

serviceCall(dbResults, (error, serviceResults) => {

console.log(result);

done(error, serviceResults);

});

});

});

}The specific pattern of using deeply-nested callbacks in this manner is commonly referred to as “callback hell”, because it makes the code less readable and hard to maintain.

Luckily, now that promises are part of the JavaScript language, the same code could be written in a more elegant and maintainable manner:

function handler() {

return validateParams()

.then(dbQuery)

.then(serviceCall)

.then(result => {

console.log(result);

return result;

});

}Even more recently, JavaScript gained support for async functions. The above asynchronous code can now be written in a way that looks very similar to synchronous code:

async function handler() {

await validateParams();

const dbResults = await dbQuery();

const results = await serviceCall(dbResults);

console.log(results);

return results;

}With async functions, the code becomes more succinct, and the control and data flow are a lot easier to follow, despite the fact that the execution is still asynchronous. (Note that the JavaScript execution still happens in a single thread, meaning async functions don’t end up creating physical threads themselves.)

From event listener callbacks to async iteration #

Another asynchronous paradigm that’s especially common in Node.js is that of ReadableStreams. Here’s an example:

const http = require("http");

http

.createServer((req, res) => {

let body = "";

req.setEncoding("utf8");

req.on("data", chunk => {

body += chunk;

});

req.on("end", () => {

res.write(body);

res.end();

});

})

.listen(1337);This code can be a little hard to follow: the incoming data is processed in chunks that are only accessible within callbacks, and the end-of-stream signaling happens inside a callback too. It’s easy to introduce bugs here when you don’t realize that the function terminates immediately and that the actual processing has to happen in the callbacks.

Fortunately, a cool new ES2018 feature called async iteration can simplify this code:

const http = require("http");

http

.createServer(async (req, res) => {

try {

let body = "";

req.setEncoding("utf8");

for await (const chunk of req) {

body += chunk;

}

res.write(body);

res.end();

} catch {

res.statusCode = 500;

res.end();

}

})

.listen(1337);Instead of putting the logic that deals with the actual request processing into two different callbacks — the 'data' and the 'end' callback — we can now put everything into a single async function instead, and use the new for await…of loop to iterate over the chunks asynchronously. We also added a try-catch block to avoid the unhandledRejection problem[1].

You can already use these new features in production today! Async functions are fully supported starting with Node.js 8 (V8 v6.2 / Chrome 62), and async iterators and generators are fully supported starting with Node.js 10 (V8 v6.8 / Chrome 68)!

Async performance improvements #

We’ve managed to improve the performance of asynchronous code significantly between V8 v5.5 (Chrome 55 & Node.js 7) and V8 v6.8 (Chrome 68 & Node.js 10). We reached a level of performance where developers can safely use these new programming paradigms without having to worry about speed.

The above chart shows the doxbee benchmark, which measures performance of promise-heavy code. Note that the charts visualize execution time, meaning lower is better.

The results on the parallel benchmark, which specifically stresses the performance of Promise.all(), are even more exciting:

We’ve managed to improve Promise.all performance by a factor of 8×.

However, the above benchmarks are synthetic micro-benchmarks. The V8 team is more interested in how our optimizations affect real-world performance of actual user code.

The above chart visualizes the performance of some popular HTTP middleware frameworks that make heavy use of promises and async functions. Note that this graph shows the number of requests/second, so unlike the previous charts, higher is better. The performance of these frameworks improved significantly between Node.js 7 (V8 v5.5) and Node.js 10 (V8 v6.8).

These performance improvements are the result of three key achievements:

- TurboFan, the new optimizing compiler 🎉

- Orinoco, the new garbage collector 🚛

- a Node.js 8 bug causing

awaitto skip microticks 🐛

When we launched TurboFan in Node.js 8, that gave a huge performance boost across the board.

We’ve also been working on a new garbage collector, called Orinoco, which moves garbage collection work off the main thread, and thus improves request processing significantly as well.

And last but not least, there was a handy bug in Node.js 8 that caused await to skip microticks in some cases, resulting in better performance. The bug started out as an unintended spec violation, but it later gave us the idea for an optimization. Let’s start by explaining the buggy behavior:

const p = Promise.resolve();

(async () => {

await p;

console.log("after:await");

})();

p.then(() => console.log("tick:a")).then(() => console.log("tick:b"));The above program creates a fulfilled promise p, and awaits its result, but also chains two handlers onto it. In which order would you expect the console.log calls to execute?

Since p is fulfilled, you might expect it to print 'after:await' first and then the 'tick's. In fact, that’s the behavior you’d get in Node.js 8:

Although this behavior seems intuitive, it’s not correct according to the specification. Node.js 10 implements the correct behavior, which is to first execute the chained handlers, and only afterwards continue with the async function.

This “correct behavior” is arguably not immediately obvious, and was actually surprising to JavaScript developers, so it deserves some explanation. Before we dive into the magical world of promises and async functions, let’s start with some of the foundations.

Tasks vs. microtasks #

On a high level there are tasks and microtasks in JavaScript. Tasks handle events like I/O and timers, and execute one at a time. Microtasks implement deferred execution for async/await and promises, and execute at the end of each task. The microtask queue is always emptied before execution returns to the event loop.

For more details, check out Jake Archibald’s explanation of tasks, microtasks, queues, and schedules in the browser. The task model in Node.js is very similar.

Async functions #

According to MDN, an async function is a function which operates asynchronously using an implicit promise to return its result. Async functions are intended to make asynchronous code look like synchronous code, hiding some of the complexity of the asynchronous processing from the developer.

The simplest possible async function looks like this:

async function computeAnswer() {

return 42;

}When called it returns a promise, and you can get to its value like with any other promise.

const p = computeAnswer();

// → Promise

p.then(console.log);

// prints 42 on the next turnYou only get to the value of this promise p the next time microtasks are run. In other words, the above program is semantically equivalent to using Promise.resolve with the value:

function computeAnswer() {

return Promise.resolve(42);

}The real power of async functions comes from await expressions, which cause the function execution to pause until a promise is resolved, and resume after fulfillment. The value of await is that of the fulfilled promise. Here’s an example showing what that means:

async function fetchStatus(url) {

const response = await fetch(url);

return response.status;

}The execution of fetchStatus gets suspended on the await, and is later resumed when the fetch promise fulfills. This is more or less equivalent to chaining a handler onto the promise returned from fetch.

function fetchStatus(url) {

return fetch(url).then(response => response.status);

}That handler contains the code following the await in the async function.

Normally you’d pass a Promise to await, but you can actually wait on any arbitrary JavaScript value. If the value of the expression following the await is not a promise, it’s converted to a promise. That means you can await 42 if you feel like doing that:

async function foo() {

const v = await 42;

return v;

}

const p = foo();

// → Promise

p.then(console.log);

// prints `42` eventuallyMore interestingly, await works with any “thenable”, i.e. any object with a then method, even if it’s not a real promise. So you can implement funny things like an asynchronous sleep that measures the actual time spent sleeping:

class Sleep {

constructor(timeout) {

this.timeout = timeout;

}

then(resolve, reject) {

const startTime = Date.now();

setTimeout(() => resolve(Date.now() - startTime), this.timeout);

}

}

(async () => {

const actualTime = await new Sleep(1000);

console.log(actualTime);

})();Let’s see what V8 does for await under the hood, following the specification. Here’s a simple async function foo:

async function foo(v) {

const w = await v;

return w;

}When called, it wraps the parameter v into a promise and suspends execution of the async function until that promise is resolved. Once that happens, execution of the function resumes and w gets assigned the value of the fulfilled promise. This value is then returned from the async function.

await under the hood #

First of all, V8 marks this function as resumable, which means that execution can be suspended and later resumed (at await points). Then it creates the so-called implicit_promise, which is the promise that is returned when you invoke the async function, and that eventually resolves to the value produced by the async function.

Then comes the interesting bit: the actual await. First the value passed to await is wrapped into a promise. Then, handlers are attached to this wrapped promise to resume the function once the promise is fulfilled, and execution of the async function is suspended, returning the implicit_promise to the caller. Once the promise is fulfilled, execution of the async function is resumed with the value w from the promise, and the implicit_promise is resolved with w.

In a nutshell, the initial steps for await v are:

- Wrap

v— the value passed toawait— into a promise. - Attach handlers for resuming the async function later.

- Suspend the async function and return the

implicit_promiseto the caller.

Let’s go through the individual operations step by step. Assume that the thing that is being awaited is already a promise, which was fulfilled with the value 42. Then the engine creates a new promise and resolves that with whatever’s being awaited. This does deferred chaining of these promises on the next turn, expressed via what the specification calls a PromiseResolveThenableJob.

Then the engine creates another so-called throwaway promise. It’s called throwaway because nothing is ever chained to it — it’s completely internal to the engine. This throwaway promise is then chained onto the promise, with appropriate handlers to resume the async function. This performPromiseThen operation is essentially what Promise.prototype.then() does, behind the scenes. Finally, execution of the async function is suspended, and control returns to the caller.

Execution continues in the caller, and eventually the call stack becomes empty. Then the JavaScript engine starts running the microtasks: it runs the previously scheduled PromiseResolveThenableJob, which schedules a new PromiseReactionJob to chain the promise onto the value passed to await. Then, the engine returns to processing the microtask queue, since the microtask queue must be emptied before continuing with the main event loop.

Next up is the PromiseReactionJob, which fulfills the promise with the value from the promise we’re awaiting — 42 in this case — and schedules the reaction onto the throwaway promise. The engine then returns to the microtask loop again, which contains a final microtask to be processed.

Now this second PromiseReactionJob propagates the resolution to the throwaway promise, and resumes the suspended execution of the async function, returning the value 42 from the await.

Summarizing what we’ve learned, for each await the engine has to create two additional promises (even if the right hand side is already a promise) and it needs at least three microtask queue ticks. Who knew that a single await expression resulted in that much overhead?!

Let’s have a look at where this overhead comes from. The first line is responsible for creating the wrapper promise. The second line immediately resolves that wrapper promise with the awaited value v. These two lines are responsible for one additional promise plus two out of the three microticks. That’s quite expensive if v is already a promise (which is the common case, since applications normally await on promises). In the unlikely case that a developer awaits on e.g. 42, the engine still needs to wrap it into a promise.

As it turns out, there’s already a promiseResolve operation in the specification that only performs the wrapping when needed:

This operation returns promises unchanged, and only wraps other values into promises as necessary. This way you save one of the additional promises, plus two ticks on the microtask queue, for the common case that the value passed to await is already a promise. This new behavior is currently implemented behind the --harmony-await-optimization flag in V8 (starting with V8 v7.1). We’ve proposed this change to the ECMAScript specification as well; the patch is supposed to be merged once we are sure that it’s web-compatible.

Here’s how the new and improved await works behind the scenes, step by step:

Let’s assume again that we await a promise that was fulfilled with 42. Thanks to the magic of promiseResolve the promise now just refers to the same promise v, so there’s nothing to do in this step. Afterwards the engine continues exactly like before, creating the throwaway promise, scheduling a PromiseReactionJob to resume the async function on the next tick on the microtask queue, suspending execution of the function, and returning to the caller.

Then eventually when all JavaScript execution finishes, the engine starts running the microtasks, so it executes the PromiseReactionJob. This job propagates the resolution of promise to throwaway, and resumes the execution of the async function, yielding 42 from the await.

This optimization avoids the need to create a wrapper promise if the value passed to await is already a promise, and in that case we go from a minimum of three microticks to just one microtick. This behavior is similar to what Node.js 8 does, except that now it’s no longer a bug — it’s now an optimization that is being standardized!

It still feels wrong that the engine has to create this throwaway promise, despite being completely internal to the engine. As it turns out, the throwaway promise was only there to satisfy the API constraints of the internal performPromiseThen operation in the spec.

This was recently addressed in an editorial change to the ECMAScript specification. Engines no longer need to create the throwaway promise for await — most of the time[2].

Comparing await in Node.js 10 to the optimized await that’s likely going to be in Node.js 12 shows the performance impact of this change:

async/await outperforms hand-written promise code now. The key takeaway here is that we significantly reduced the overhead of async functions — not just in V8, but across all JavaScript engines, by patching the spec[3].

Improved developer experience #

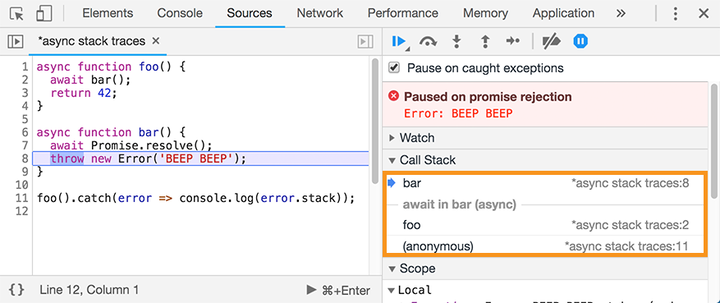

In addition to performance, JavaScript developers also care about the ability to diagnose and fix problems, which is not always easy when dealing with asynchronous code. Chrome DevTools supports async stack traces, i.e. stack traces that not only include the current synchronous part of the stack, but also the asynchronous part:

This is an incredibly useful feature during local development. However, this approach doesn’t really help you once the application is deployed. During post-mortem debugging, you’ll only see the Error#stack output in your log files, and that doesn’t tell you anything about the asynchronous parts.

We’ve recently been working on zero-cost async stack traces which enrich the Error#stack property with async function calls. “Zero-cost” sounds exciting, doesn’t it? How can it be zero-cost, when the Chrome DevTools feature comes with major overhead? Consider this example where foo calls bar asynchronously, and bar throws an exception after awaiting a promise:

async function foo() {

await bar();

return 42;

}

async function bar() {

await Promise.resolve();

throw new Error("BEEP BEEP");

}

foo().catch(error => console.log(error.stack));Running this code in Node.js 8 or Node.js 10 results in the following output:

$ node index.js

Error: BEEP BEEP

at bar (index.js:8:9)

at process._tickCallback (internal/process/next_tick.js:68:7)

at Function.Module.runMain (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:745:11)

at startup (internal/bootstrap/node.js:266:19)

at bootstrapNodeJSCore (internal/bootstrap/node.js:595:3)Note that although the call to foo() causes the error, foo is not part of the stack trace at all. This makes it tricky for JavaScript developers to perform post-mortem debugging, independent of whether your code is deployed in a web application or inside of some cloud container.

The interesting bit here is that the engine knows where it has to continue when bar is done: right after the await in function foo. Coincidentally, that’s also the place where the function foo was suspended. The engine can use this information to reconstruct parts of the asynchronous stack trace, namely the await sites. With this change, the output becomes:

$ node --async-stack-traces index.js

Error: BEEP BEEP

at bar (index.js:8:9)

at process._tickCallback (internal/process/next_tick.js:68:7)

at Function.Module.runMain (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:745:11)

at startup (internal/bootstrap/node.js:266:19)

at bootstrapNodeJSCore (internal/bootstrap/node.js:595:3)

at async foo (index.js:2:3)In the stack trace, the topmost function comes first, followed by the rest of the synchronous stack trace, followed by the asynchronous call to bar in function foo. This change is implemented in V8 behind the new --async-stack-traces flag.

However, if you compare this to the async stack trace in Chrome DevTools above, you’ll notice that the actual call site to foo is missing from the asynchronous part of the stack trace. As mentioned before, this approach utilizes the fact that for await the resume and suspend locations are the same — but for regular Promise#then() or Promise#catch() calls, this is not the case. For more background, see Mathias Bynens’s explanation on why await beats Promise#then().

Conclusion #

We made async functions faster thanks to two significant optimizations:

- the removal of two extra microticks, and

- the removal of the

throwawaypromise.

On top of that, we’ve improved the developer experience via zero-cost async stack traces, which work with await in async functions and Promise.all().

And we also have some nice performance advice for JavaScript developers:

- favor

asyncfunctions andawaitover hand-written promise code, and - stick to the native promise implementation offered by the JavaScript engine to benefit from the shortcuts, i.e. avoiding two microticks for

await.

Thanks to Matteo Collina for pointing us to this issue. ↩︎

V8 still needs to create the

throwawaypromise ifasync_hooksare being used in Node.js, since thebeforeandafterhooks are run within the context of thethrowawaypromise. ↩︎As mentioned, the patch hasn’t been merged into the ECMAScript specification just yet. The plan is to do so once we’ve made sure that the change doesn’t break the web. ↩︎